Welcome to Creative\\Proofing, a space for hopeful, creative people learning to live wisely by asking questions about the good life: what it is, how to design our own, and how to live it well.

This newsletter is built on the hope of reciprocal generosity: I want to share what I find beautiful and meaningful, and I'd love for you to do the same. If you're inspired by anything I share, it would mean so much if you shared it with others, subscribed, dropped me a line and let me know, or paid according to the value it has for you. No matter what, I hope we can create and learn together.

Reflection

With the development of The Liminal Space framework and visual, and discerning how we might move about within it, I'm looking back at significant periods of my life, reflecting on where I've been, where I've traveled to, and what I carry with me still.

It's hard to believe twelve years have passed since I was diagnosed with cancer, and about ten years since I wrote this essay. I see even more how the diagnosis thrust me into a journey with a distinct before and after, the ways in which I'd always envisioned the trajectory of my life disintegrating within a span of several weeks. The stability of my days, the predictable routine of work and family and friends, was suddenly exposed as more fragile and uncertain than I'd realized.

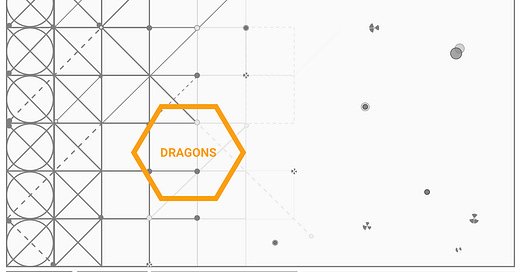

When this happens, when you find yourself moving from stability to the liminal, your life, and how you've understood it so far, begins to feel distant, trapped behind a barrier of glass: visible and recognizable, but no longer familiar or accessible. It no longer makes sense to you, and taking a next step feels fraught with terror, behemoth dragons suddenly springing out of the woodwork to stand on the path ahead. Your old life becomes a painful void, because it's lost to you forever, and no hammer exists that can break the glass between now and then.

So the task, the job, the quest and question of your life becomes: how do I move forward? How do I set my face to this unknown, unexpected path, and what kind of journey will I make of it? How will I meet the dragons in my way?

Let's be hopeful, creative, and wise — together.

Shalom,

Megan.

The Other Side of Normal, Pt. 1

originally published at The Other Journal, Oct. 18, 2012

“Fearlessness is better than a faint heart for any man who puts his nose out of doors. The length of my life and the day of my death were fated long ago.”1—I read these lines in the Norse epic poem For Skirnis as a child and have remembered them often since. I steeped myself in Norse and Celtic mythologies, and I remain impressed by the fierceness of those warriors whose legendary tales forged cultures. I always wanted to ride out, meet the enemy, slay the dragon. Well, I wanted the sword and the horse, maybe not so much the dragon. (Messy creatures, dragons. Always wreaking havoc and tearing up things.)

More than anything, I longed to emulate the delight, the unwavering readiness for battle that I saw in Finn MacCool or Beowulf as they met monsters head-on. Such fatalistic readiness stemmed from the hope of achieving immortality through a glorious, epic death (which was not something I hoped for), yet I found that clear-eyed courage attractive. You know you will end in death, but you ride out to meet it anyway. You hope to die for something worthwhile.

We encounter so many cruel enemies in this world. Let us also meet brave knights and hear of heroic courage. Our heroes often show us what we lack and find attractive in others. As a child, I carried within myself both the fear and the longing to become someone else, someone different. I longed for courage, yet I feared the path that would take me to it. In riding out to face whatever monsters blocked the path of his journey, Skírnir, the hero of that Norse poem, embodied the courage I failed to find in myself, once upon a time.

“Fearlessness is better than a faint heart”—I returned to these words over and over again in 2009, after the discovery of a lump at the base of my neck during a doctor’s exam. The doctor asked me, “Do you ever feel that nodule there?” I chuckled, “Riiiight. Because I always go around massaging my neck.” The doctor had his assistant schedule an MRI for that afternoon. I felt a tremor in my lower stomach, the body’s reaction to uncertainty. What did he expect to find?

Later, the table slid into the MRI machine. I tried to focus on breathing normally, but that encompassing, confining tube felt like a terrible mockery of a birth canal. Let’s just say it took all my energy and effort to avoid erupting into ear-splitting shrieks. I tried reciting nursery rhymes and favorite songs. Yeats’s “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” appeared, as did Matthew 6, Psalm 23, and the “Litany against Fear” from Dune. Desperation breeds strange bedfellows.

Expelled from the tube, and then, rebirth—but into what life? Everything remained normal, except . . . not. Yet I wasn’t even sure what had changed. The whisper of it curled around me, settling its furtive weight on my shoulders. Only sleep let me return to the ordinary time I’d known just a few days prior. In the days and weeks after the MRI, as I waited for the test results to come back, I came to dread waking up, wondering what was incubating itself within my body. Those initial moments of forgetfulness each morning, when the world seems much less cold, when potential has yet to turn into a dirty word and that weighted whisper has yet to settle back around your shoulders—that forgetfulness feels foolish. How do you get up? How do you go to work, eat your lunch, have a normal day?

Three years later, I still don’t know how a normal day happens, but somehow, it does. Rainer Maria Rilke’s advice to “be patient to what is unsolved in your heart,” to live with the as-yet unanswered questions, proved both difficult and freeing. Rather than grappling with what might happen—and I starred in all sorts of imagined deathbed scenes—I asked myself how I felt about the possibility that I might die sooner than I’d planned. C. S. Lewis wrote that we “live in time, but we are destined for eternity.”2 Did I believe that? I lived into that question every day, wrestled with it in the only way I knew how: pen on paper, pouring words into poems, into prayers.

Questions

breathe in

this dark

space between

rib and lungand wait

wings quivering

fragile in words

unspoken whiteeach one fluttering

out my throata pale swarm

taking flight

From the beginning, family and friends supported me. Yet I also learned the double-edged sword of encouragement in suffering: sometimes those who intended to provide hope caused wounds more painful than the one they tried to ease. It hurt to close myself off to hope as much as it hurt to hold on to it in the first place. I never quite let go of all hope, though perhaps it would be better to say that hope never let go of me.

Finally, a month after first contact, the diagnosis came: papillary carcinoma, a slow-growing, easily treatable form of thyroid cancer. I promptly named it Fredi the Cancerous Bastard. Plans for treatment moved with startling swiftness. My doctor referred me to the best head and neck surgeon at Georgetown Hospital, who scheduled my surgery for the next month. A month doesn’t sound so long, but knowing that I had cancer the size of a golf ball burrowing into my body, I wanted it out as soon as possible.

If I had my druthers, no one would have known about Fredi or the surgery. I wanted to live and work and play and then show up at the hospital and deal with it there. I didn’t want to receive sympathy from others—kindness hurt. Normal buffered. Even as I craved others’ blessings, I quaked at the thought of acknowledging the monster in my way. But if I said nothing, then how could I live on the prayers I so desperately needed? Pen and paper, poems and prayers, once again.

Kindness

please

speak in

matters of fact

let me copy

and correlate

a thousand and one

pagesplease

shutter

that window

between your

life and mine

overlook

these ashes

smudged across

my throatplease

withdraw

your alms

so freely

and awfully

offered

my beggaring heart

Part II

See Snorre Sturleson, “The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigfusson; and the Younger Eddas of Snorre Sturleson,” Project Gutenberg, Last modified 2005. Accessed October 8, 2012.

Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1993), 35; and Lewis, The Screwtape Letters (New York, NY: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, 1996), 61.